Federal prosecution for conspiracy to sell illegal drugs often reaches past the leaders of drug cartels and their mid-level managers. The target of a federal investigation may well be the regional distributors and their retailers who deliver illegal drugs for larger organizations. Federal prosecution often starts with the street dealer and his confederates. However, when the government prosecutes an end-user who has no ties to the organization that sells drugs, the “buyer-seller relationship defense” should be raised.

To establish a conspiracy the government must prove that: (1) an agreement existed between two or more persons to violate federal narcotics law, (2) the defendant knew of the existence of the agreement, and (3) the defendant voluntarily participated in the conspiracy. “The government does not have to prove that the defendant intended to commit the underlying offense himself/herself.” Salinas v. United States, 522 U.S. 52, 64, 118 S.Ct. 469, 139 L.Ed.2d 352 (1997). Instead, “[i]f conspirators have a plan which calls for some conspirators to perpetrate the crime and others to provide support, the supporters are as guilty as the perpetrators.” Id. at 64. Co-conspirators may also be liable for the substantive offenses committed by other members of the conspiracy in furtherance of the common plan. United States v. Lopez, 979 F.2d 1024, 1031 (5th Cir.1992), cert. denied, 508 U.S. 913, 113 S.Ct. 2349, 124 L.Ed.2d 258 (1993). Therefore, a defendant can be liable for a possession conviction on the basis of both his constructive possession over the contraband and his status as a co-conspirator. See id.

While the conspiracy statute is broad and far-reaching, a conspiracy requires more than just a buyer-seller relationship between the defendant and another person. A drug user who buys illegal drugs does not enter into a conspiracy with the seller of illegal drugs simply because the buyer resells drugs to others, even if the seller knows that the buyer intends to resell the drugs. Even a drug purchase of large quantities of illegal drugs may not be enough to establish a conspiracy. “It is not enough for the evidence merely to establish a climate of activity that reeks of something foul.” United States v. Galvan, 693 F.2d 417, 419 (5th Cir. 1982) quoting United States v. Wieschenberg, 604 F.2d 326, 332 (5th Cir.1979). Similarly, an allegation of conscious parallelism or parallel business conduct, without factual allegations “suggesting agreement,” does not state a claim with respect to antitrust conspiracy and mere proof of “conscious parallelism” or parallel business behavior is insufficient to prevail on a claim for antitrust conspiracy. Occasional credit sales are not necessarily inconsistent with a buyer-seller relationship. Evidence of sporadic purchases on credit would not create a de facto conspiracy.

To prove conspiracy, the government must prove an “agreement” between the defendant and the seller that would characterize their relationship as more than a “buyer-seller” arrangement. To establish such an agreement, the government must prove that the defendant had the deliberate, knowing, specific intent to join and work for the conspiracy. Evidence of the agreement may be direct or circumstantial and can rely on a variety of sources including telephone and bank records, buying patterns, personal relationships with the seller, and evidence of profit sharing or personal use.

Multiple buyer-seller transactions are typical for drug users but such transactions do not prove that a defendant participated in a conspiratorial agreement to distribute drugs. “Although every drug deal involves an unlawful agreement to exchange drugs, courts have held that a buyer-seller arrangement cannot by itself be the basis of a conspiracy conviction because there is no common purpose: The buyer’s purpose is to buy; the seller’s purpose is to sell.” United States v. Long, 748 F.3d 322, 325 (7th Cir.2014) (internal quotation marks omitted).

Defense counsel should challenge any allegation of conspiracy to distribute narcotics when there is no agreement to work toward some common objective and the connection can fairly be described as a buyer-seller relationship. In such cases, the government should be compelled to abandon the conspiracy allegation in the indictment.

Austin Criminal Defense lawyer

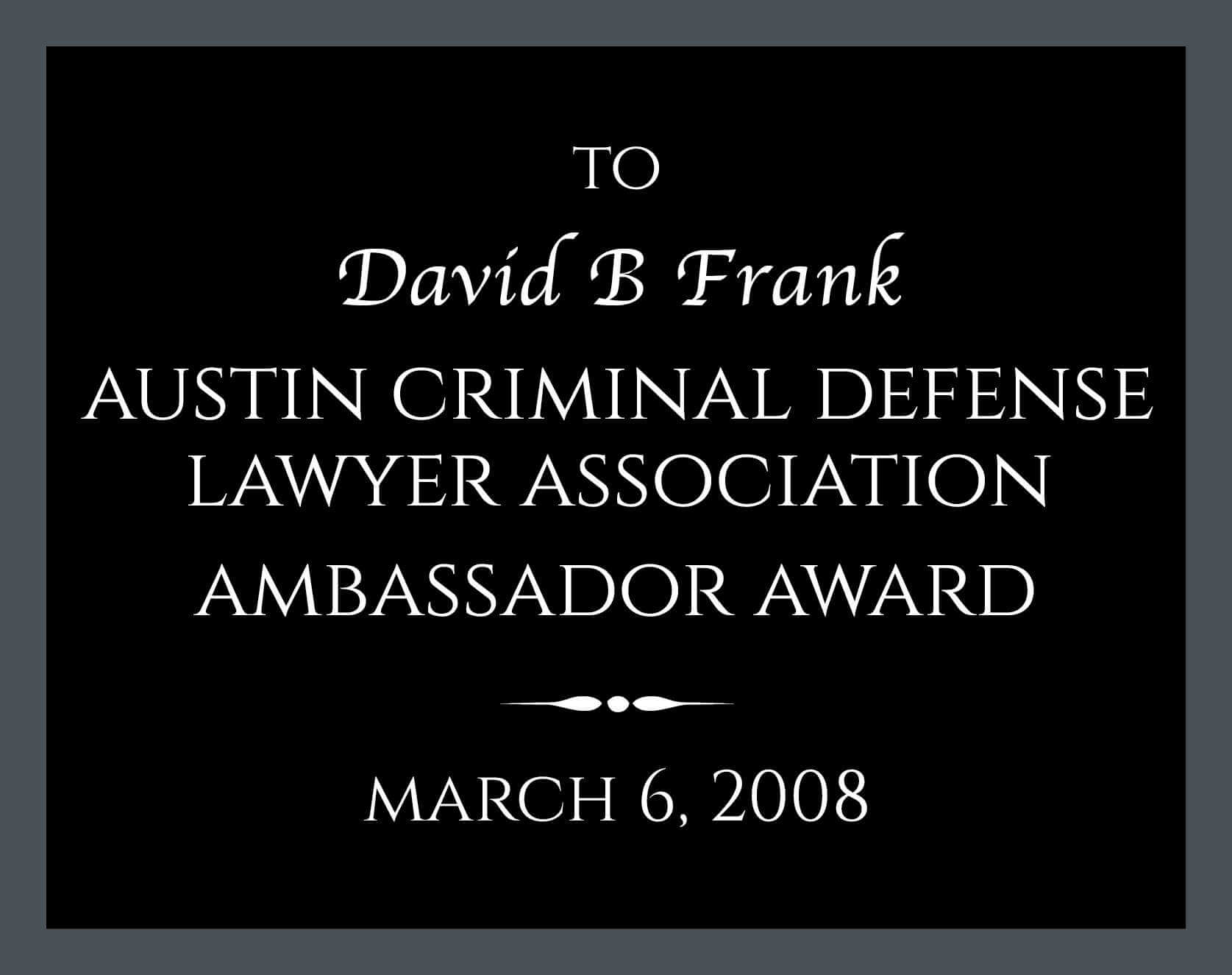

David Frank has been an Austin Criminal Defense lawyer since 1993. He is Board Certified in Criminal Law by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization. An attorney who is Board Certified by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization in Criminal Law must have experience in the preparation and trial of serious criminal matters. The attorney must also have extensive knowledge of state and federal constitutional law, evidence, procedure and penal laws involved in the trial of these matters.

Leave a Reply